Charlie Pountney (CP): So, welcome one and all to this highly anticipated discussion on Beyond Oloroso. This is very exciting that we are finally live. This is Charlie Pountney from Ethimex Limited and I’m joined by Richard Bayles our head of division for Ethimex Cask, so again thanks for joining this live stream.

So, as an introduction to who we are here at Ethimex, we are a specialist in worldwide bulk distribution of alcohol and speciality spirits and we’ve been around since 1999, proudly a UK privately run company. We consider ourselves experts in sourcing and supply of global spirits around the world and also wooden casks, which brings me nicely onto introducing Richard Bayles. Richard is our head of Latin America business at Ethimex, heading up sourcing projects and the sales operation. He is also our rum and agave spirits expert and has been leading the casks division at Ethimex for over 10 years. He’s got a lot of experience with sourcing barrels, setting up cooperage projects around the world and lots of experience working on projects with famous distilleries.

Oloroso fortified wine casks are probably the preeminent and most common fortified wine cask to be used in spirits maturation where, predominantly, we’re talking about whisky maturation I suppose. What we wanted to do is take this opportunity to give people a bit more insight into alternatives because there’s a lot of different flavours and styles that can come from looking outside of oloroso casks. We will be giving you an introduction to the different fortified wine styles and some of the flavours that you can expect to find from their barrels. We hope to provide some inspiration for people who working at in NPD, in production or even in spirits marketing about some things that other people are doing that might be of interest.

Richard and I have also got a few of the samples in front of us to help guide us through the flavours from the different fortified wines. The reason we’re tasting is basically because its the only way to explain what the wine in the casks taste like. That’s how a whisky maker can start to think about what casks might match with their spirit.

We’re going to start off here with fortified wine. What does it mean and why do fortified wines exist in the first place?

Richard Bayles (RB): Right thanks Charlie and thanks for having me along it’s a pleasure to be here. Fortified wine is a still wine (or was a still wine) which has had high proof or high strength spirit added to it.

There’s two principle winemaking reasons why this is done. The first is rooted in history. Adding spirits to wine basically preserved and protects the wine from unwanted oxidative effects. For a still wine this could be acid / vinegar taste which you don’t want in any significant quantity in a wine. So adding ethol alcohol in one form or another in this case normally a grape spirit stops those negative opposite effects and just allows what we might call positive oxidative evolution.

The second reason which is very important for most or least many fortified wines around the world is arresting the fermentation so basically if you put high strength spirit into wine and take the ABV up to about 15% in above, you’re basically interrupting and killing off the yeast and stopping fermentation. This will leave plenty of residual sugar left in in the wine. So it’s a way of controlling the sweetness levels and creating a sweet dessert wine.

This doesn’t apply to most sherries though (which are typically dry) but there are a lot of sweet pudding wines out there which are created using the addition of alcohol.

Fortified wines mostly come from Europe which is a sort of Mecca for fortified wines. Originating from the Mediterranean and Southern Europe. We’ve got Vins Doux Naturels from France this is a whole category of fortified wines principally muscats.

You have Porto or Port of course, which is northern Portugal. You have sherry or Jerez and Madeira and then over in Sicily you have Marsala which is Western Sicily. So these are the principle styles and traditions of fortified wine making which will go into one by one.

CP: We should start with oloroso, where it’s from how it’s made? What flavours would we be expecting from casks?

RB: Sure Oloroso is, let’s be honest, it’s arguably the best casks for finishing a good whisky good rum. I’ve even seen tequilas out there using a bit of oloroso. But we’re trying to beyond that as you said. Oloroso is a fully oxidised style of Sherry. Sherries come in different levels of oxidisation but also have been exposed to the elements as being exposed to oxygen in the air for a long period of time minimum typically 10 years minimum but certainly twenty 30-40 years via the Solera system.

What you get of course is that classic flavour profile… those dried fruits that the intensity and the complexity and obviously the rancio notes the nuttiness all of this comes from the the highly oxidative style of Sherry.

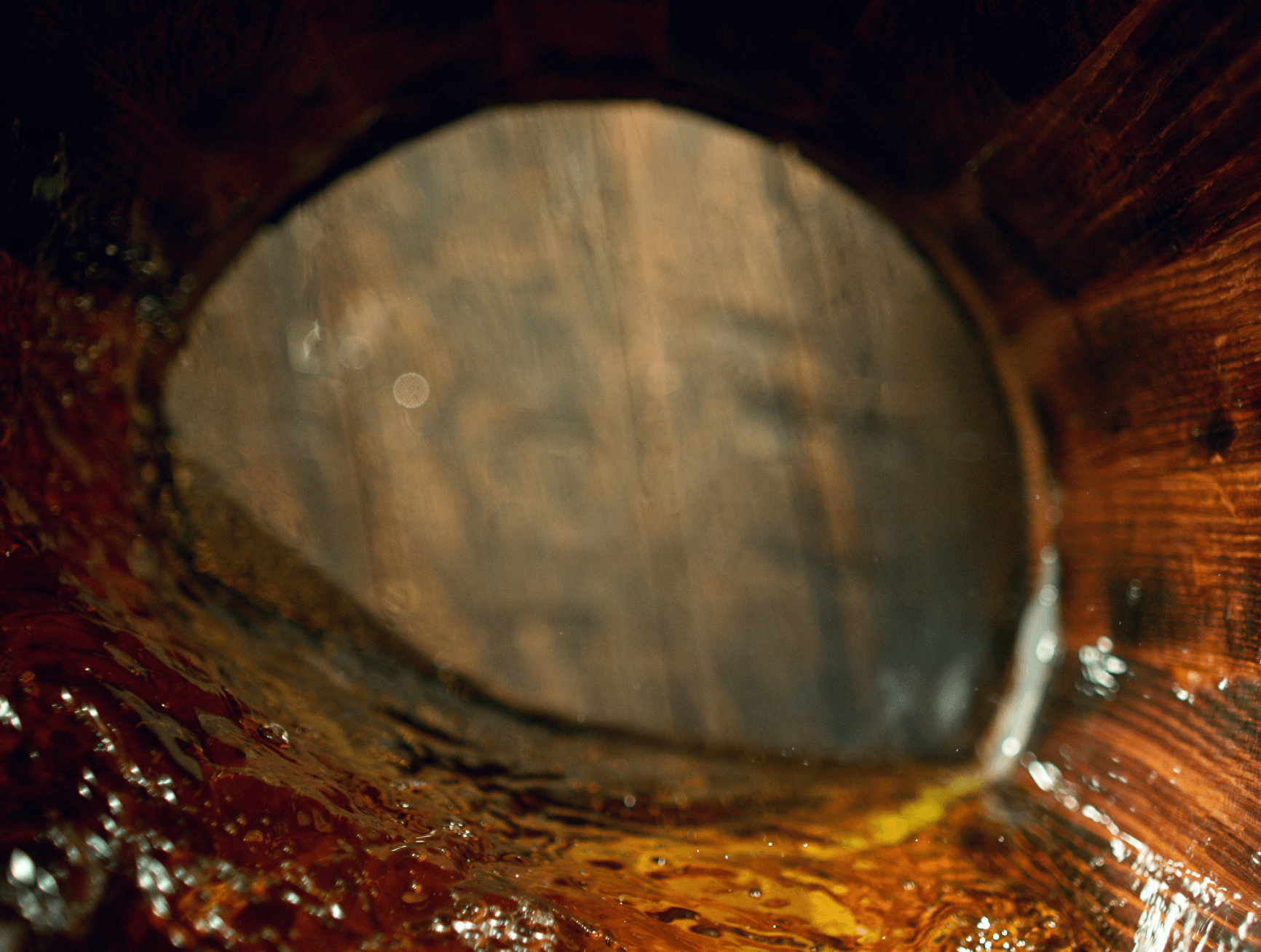

The solera is it used for all Sherry styles of ageing which has been used for a couple of hundred years. It’s very simple in a sense. The solera is the casks which is stored on the ground level all along the floor. They hold the finished wine the one that’s ready for bottling So what happens sort of working in the wrong direction…. they will take up to 30% of the solera cask wine and bottle it off. This will allow them to move the same amount of wine from the layer above and bring it down and put it into the solera casks. The same goes with the second solera at the top, where they bring up to 33% per year of that liquid down to the second layer below and this way you get something called a ‘perpetual system’ or ‘dynamic ageing’ or sometimes called fractional blending. It’s a very good way of developing particular styles but it ultimately ends up in a very, very well aged product because you literally very tiny amount of old Sherry swimming around in the solera sometimes up to 100 years old or more.

CP: So how long would these casks be used in in a typical cask? These types of ex-solera casks are very hard to come by, the reason is because there’s equilibrium now between production. There are fewer bodegas being closed down and sold off. The casks could be as young as 10 or 20 years old but typically there could be 40-50 hundred years old even 150 years old. When a barrel falls to bits that’s when they get rid of it or they get repaired and often they repair them. They want to keep the barrels as long as possible as they do not want any wood influence to come from the casks into the sherry. The older the better really.

CP: What flavours would we expect these casks to impart on ageing spirits?

RB: It’s the classic colour profile, this concept of rancio literally means rancid in Spanish but there’s the nuances of meaning it’s a positive thing in the Spanish language in the context of the wine is this sort of you know nutty notes coming through is very complex oxidised notes so you’re going to get that nuttiness, a lot of nuttiness. In oloroso of course people talk about something like a pudding spice mix and Christmas cake a lot. You do get these dark fruit dried fruit kind of flavours coming through a lot and that travels very well into the into the whisky.

People assume that Sherry is sweet but sherry is bone dry. I’d say it is the driest of all fortified wine styles and we’re going to run through some of them now some of them are slightly drier than others but all devoid of any residual sugar and also not much glycerol which often gives a sweet to the rounded feel so they’re very dry and what’s interesting is that the barrels give completely different flavours and you might expect.

CP: What are the other different types of Sherry, what makes them different?

RB: OK – firstly fino and manzanilla sherries, we’ll start with that. The thing about the dry sherries is they all start with the same grape and the same wine or very, very similar wine made from the same grape. It’s just a question of how that reacts after that and how they are fortified and so forth.

These are biologically aged sherries – they’re very similar so we can put them in one category but there are nuances between them. What happens is the wine which is produced from the Palomino grape to about 10.5 to 11% ABV before fortification. It’s already bone dry at that point so it’s fortified not for its strength but to kind of protect it from oxidation. It’s fortified in such a way up to just 15% to kill off the yeast However we still want another kind of yeast to form on the top of the surface of the liquid which is called flor. It’s fluffy scummy looking, almost like a mould which initially floats on top of the surface and eventually covers the whole surface in the barrel in the cask. This layer protects the wine from oxygen completely, it’s like an almost 100% seal and it feeds off the alcohol creating acetaldehyde. This bring a very crisp appley, sharp, zingy character. This is called biological ageing basically there’s no oxidation in the traditional sense but it is still maturing developing rancio notes under this veil of flor.

So the difference between fino and manzanilla is more or less the location where it’s stored. So it’s an appellation thing. Some will pick up some more maritime notes and salinity from the air, so you get this kind of very savoury.

[Drinking the manzanilla]

CP: It’s quite dry and sharp. Kind of green apple for sure little bit of musty notes, not like many other age spirits.

RB: Slightly bruised apple notes as well… like when apple goes slightly brown or when you cut into apple. You’ll notice is bone dry it really is bone dry. Most people describe this as an acidic wine but in fact it’s actually quite low acidity it’s just very dry. One of the reasons is the glycerol has been eaten/consumed by the flor so it’s taken away all of that all of that sort of rounded sweetness. I would say definitely I get to cheesy notes. There’s like a kind of parmesan cheese flavour which mean this goes very well with a Spanish ham and seafood

Manzanilla is very similar to fino with less of the salinity possibly it can be more rounded. Some people might disagree because there’s perhaps a touch more bitterness in fino because the floor is less prolific inland, whereas by the sea there’s a lot of flor elements.

CP: I haven’t come across any fino or manzanilla aged spirits myself but I suppose it’s similar to kind of white wine cask in some ways?

RB: Yes, it’s a very challenging choice. It’s obviously good for ringing the changes or for label marketing. It’s a it’s a very difficult finish to try and achieve because it’s such a delicate wine. Its so delicate, that it can get overpowered and completely lost in the barrels.

CP: The next Sherry that we wanted to talk to talk about sorry was the amontillado.

RB: These are intermediate styles of Sherry. You can think of them as a progression or a stepping stone from fino all the way through to fully oxidised. So what happens with amontillado, and it depends on the winemaker, normally the on the final stage of the solera system the winemaker will decide to fortify the wine further to take it up something like 17% and what that does is kills off the flor. This isn’t about getting the yeast, its about killing off the floor which are very quickly exposed to the wild oxidation.

CP: It’s a halfway house between the two styles. On the nose to me there’s obvious oxidation but there’s still quite a bit of a fino character coming through it’s not that pronounced compared with the last one. You get darker notes like rasin coming through as well.

RB: It’s very, very dry as well so a very good wine, that’s very popular in Spain. It’s an elegant style but as you can tell yeah it’s sort of hybrid. There’s a lot of marmalade notes as well sort of like a Seville orange marmalade and with that’s with those notes coming through in in the ageing process.

It’s a good alternative for us so if you want something different to oloroso, if you wanted something fresh and interesting on your label you know it’s an option.

CP: So the next one that was on the list was palo cortado.

RB: Well, Palo Cortado is a hybrid, its. Different style and the reason is and by the way Palo traditional Palo is very rare it’s an accident of nature. These are sort of accidents that the winemaker discovers and is very pleased to find them. Basically what happens in some fino sherries, we don’t know why, but the floor sometimes just dies or it breaks up so suddenly even without the winemaker noticing it’s been exposed to oxygen. It’s probably been exposed to oxygen for quite a few years but there’ll be examples now of actually forcing this to happen, or blending stuff together trying to emulate that style. So it’s an accidental wine that sits between amontillado with no biologicial ageing.

CP: there’s an obvious brown sugar and nuttiness there.

RB: It’s a excellent example of an alternative to oloroso and it is officially a different category so you can call out on a label.

CP: Finally then is the other probably most more well known Sherry style but we see quite a lot in the UK and in finishing an ageing Pedro Ximenez.

RB: It’s very much an outlier compared to the other Sherry types we discussed. It is exposed to oxidative ageing but it’s characterised through a very high sugar content. The PX grape is harvested and put on mats out in the sun for once two weeks to really basically turn the grapes to raisins. You get this gooey must which is much higher in sugar than most grape must. In fact it’s so sweet that the fermentation doesn’t work very well for us so they end up as table wines or they fortify it up to 16 or 17% quite early on in the process. So all of that means you’re left with huge amount of residual sugar I think pretty much in the region of at least 200 grams per litre sometimes 300 sometimes more. It has a very distinctive taste as well as being extremely viscous.

CP: It’s like a like a well made gravy I would say and in your glass it’s incredibly viscous, and it almost looks like gravy as well with how dark it!

RB: That is the sugar content of course. It tastes of raisins, dates, dried fig. People talk about dried figs but I get prune juice.

CP: I’m getting a kind of molasses and treacle, almost burned on the palette.

RB: It’s real outlier, typically 18% but this one’s a bit lower this is actually 16% but typically they could be a fortified to a high degree and so they’re dangerous! Principally it used to be grown outside Jerez but it’s authorised for use in Sherry.

I was talking about the Bristol Cream sherry and PX is used as part of the formula to sweeten it. This will be the case in Harveys Cream… they’ll take some PX to add some power, complexity and sweetening ingredient.

CP: So if we talk about PX casks are these typically coming from the solera system?

RB: they are unusual and hard to source but at Ethimex we tend to specialise in ex solera casks wherever possible. However, the majority of PX casks are not true ex-solera. They have been made and ‘seasoned’ by adding another sherry into the casks for 12-24 months. For me 12-18 months is not a sufficient length of time for the sherry flavour to absorb into the wood. Especially with PX as this is a very viscous wine. We call the liquid which has absorbed into the staves ‘in drink’. In large sherry butts there can be up to 10 litres of in- drink in the cask.

CP: We have a question from No Nonsense Whisky saying that he always gets a lot of sulphur from Sherry influence whisky, do you have any idea where that might come?

RB: Yep absolutely. During the winemaking process to preserve the wine sulphur still has to be used. It is a nightmare for distillers because it doesn’t really matter so much in the wine but it’s not really something you want in your whiskey or rum. It comes on the vinification process and even at very low threshold so they’re very easily detectable. We generally spot test for sulphur and we do take a look at the wine itself that came from the barrel and test it for sulphur as well. Generally we rely on our trusted supplier partners that have a good eye for that problem. It’s not really necessarily a fault from as it’s just that using sulphur is a part and parcel of wine production that often will then continue through to the end maturation of whisky.

CP: OK the next chapter is moving away from Sherry and towards other fortified wines. So the first one we’re going to talk about is Port. Can you tell us about the production and how barrels affect maturation Rich?

RB: Yep yeah sure of course, Port is quite different in many ways to the other fortified wines particularly Sherry. Port is a blended product, its made from wine which uses grapes from lots of different vines that all often grow in the same field. The list of the port grapes grown is not quite endless but it’s a very long list of maybe 5,6,7 widely found varieties and also the wines themselves are blended between different years, different wineries so it’s a very blended product. Compared to Sherry is port is a sweet wine. Port has its fermentation interrupted quite early on maybe halfway through, sometimes earlier through fermentation. This is to maintain the sweetness of the wine by halting the fermentation. It is also to preserve the freshness of the red grapes. Port is a belting strong red wine before even before it’s fortified think of Dora wines or maybe Toro from Spain just up the river. It is a very strong characterful fruity red wine, so one of the purposes of the fortification is to also preserve that red fruit character. It’s a fairly rapid fermentation process with the skins so it brings in a lot of phenolics including tannins into the wine. Also preserves the colour which is bright red Ruby. There are two important styles of port when it comes to ageing – Ruby and Tawny port. Ruby port is traditionally aged in huge oak vats around twenty or thirty thousand litres. There’s no wood influence at all because the wood is already well seasoned but it’s also so huge that not much wood contact happens with the surface of the cask. However things are changing and there are definitely smaller producers further inland that are using smaller casks. They first season the casks for 2-3 years with normal table wine and that’s actually part of the winemaking process for still wines and then they take the barrels which would be used for red wine and start using it for port. That way a lot of the tannins and a lot of the spices has already been drawn out of the cask. Tawny Port is similar to Ruby when it starts the winemaker may adjust the process slightly but basically you’re putting a kind of ruby port into a big cask. These casks are about 600- 650L in size and are what is called a ‘port pipes’. This is the traditional method and that exposes the port to oxidation… again were into the oxidative territory. So across typically 8 to 10 years you’re starting to see a young tawny port develop. Older versions can be left in the barrel for twenty 30-40 years and the oxidation obviously changes the character as you go along. Some smaller wine makers are using smaller barrels like 225 litre wine type barrels to age their tawny port now but it’s still doing the oxidative style.

CP: So the casks which we find for maturing spirits are these smaller ones on the secondary market?

RB: Basically Portugal these 600L cask Pipes are very hard to come by. They send them out for repair as they want to hang on to them. It’s tradition but also economics because its better to hang on to them as they’ve been really, really well seasoned…. so there’s no oak influence. Most of the barrels were getting are the smaller ones (225L) but are really good for finishing spirits of course that’s both tawny and Ruby these days. We sent some Pipes to Barbados quite recently.

CP: So what influence on spirit would you get from these casks?

RB: Lets taste the ruby port. Some of the best ruby ports are the youngest ones, really young really fresh but this one we have has had a bit of time to settle in cask. In these big casks you don’t see much oxidation compared to the smaller pipes.

CP: You don’t get huge amount of those interesting oxidation characters on the nose as you said but on the on the palate it’s super berry like really strong berry flavour.

RB: Here you’re getting sometimes raspberries but I’m always thinking red plum and even dark Victoria plums, cherry as well, these kind of dark red and black fruits but it’s very fresh and lively. I’m not getting here but you sometimes get sort of floral notes sort of herbaceous green and bergamot as well but I’m not going on this example.

CP: Let’s try the tawny Port… you can immediately get more of that oxidation

RB: This is a 10 year old so this is young tawny port doesn’t mean that old, it needs to have the character of a 10 years so it means there could be some 9 year old in their 11 year old.

CP: So there is a lot more character, a much more interesting nose with kind of musty aromas.

RB: You get cooked fruit for me, it’s lighter but more robust but also got a lot more flavours going around

CP: Whereas the Ruby was big and fruity like a kind of like a Malbec or you know big bold red wine this is like a more mature lighter but like a pinot noir but just with more going on it’s quite interesting.

RB: There’s also some balsamic feel to it. They are both different animals they’re both great fortified wines. Most people would go for tawny as it’s more expensive it’s older but it’s a different style. Using Ruby port can yield impressive results for whisky and rum ageing and also you get that great colour boost from the casks. We’re working with some guys in tequila and its coming out like a rosé.

CP: I think we should move on to the Madeira?

RB: So the Madeira has interesting and distinguishing characteristics compared with other fortified wines. When wine and fortified wine was being shipped from Portugal around the world to the Southern States of America and to the Caribbean, they soon discovered that using the barrels as ballast on these ships, often on the open deck, it was noted that the wine had basically started cooking in the sun over many months when they got to the destination. It was noted that it had taken on some amazing cooked characteristics which the Portuguese liked and it became a very popular style. They started to emulate the heating process in their wineries so they just leave the casks of Madeira in very warm parts of the winery, up high in the loft or under the eaves in order to cook the wine. They have a speeded up the process for the cheaper Madeira ‘s where they actually heat the stainless steel tanks in production. So you have different grapes, normally its bone dry, similar to fino but there are varying degrees from dry to sweet. From what I have understood over the years they’re always aged, and heated in kilns or ovens. The traditional system of course doesn’t use

intervention, just the natural heat from the subtropical island with year-round warm temperatures. This one is just a 5 year old I’m getting those really cooked stewed apricots flavour. If you imagine literally throwing a lot of fruit into a pan and cooking them down and that’s a complex kind of aroma on the nose. We’ve gone kind of back to the cherry. This is a good alternative to oloroso or PX casks. Availability of madeira casks is quite limited and but the range of profiles is very exciting for the for the whisky maker.

CP: I’m getting a lot of sweet pear on the nose.

RB: If you are getting those caramelization and Maillard reaction type flavours that is actually from the heating of the wine, it’s the real thing.

CP: So moving on to the next one is masala

RB: OK so one of my favourites, also one of the most unknown fortified wines which is such a shame. By the way 75% of wine drunk in the UK at one point was fortified wine… Marsala fell out of fashion though at some point. Marsala is fantastic though there are some very interesting styles of wine. There are three ways of categorising marsala wine and when you interplay the three different ways of defining them you get a whole combination of different wines. If you like, you can define it by colour or wine making method. Ambra which means amber. It has had some cooked grape must added to it unfermented grape must gives it colour, Oloro is gold, Rubino is ruby, Vergine is virgin. The second categorisation would be on the sweetness level. So you have a ‘secco’ anyone who speaks Italian or Spanish, even Portuguese will know that means dry, there’s semi- secco (semi dry) and dolce (sweet). So there are lots of different styles coming out of the same grape which is principally Grillo. There are four or five other grapes that they use. Grillo is a white grape but nero d’avola is also used. So marsala is a is a real hidden gem it was less hidden in the past but seems to be less popular now. This is a Marsala vergine which means they can’t add any of this cooked grape must at the beginning for colour or flavour. I wouldn’t say unadulterated let’s just say it’s not been touched. It has been aged oxidatively normally, in a system called ‘in perpetuum’ which is basically a solera system. Vergine has to be 5yrs old Vergine straveccio has to be 10 years old so let’s try that quickly.

CP: I’m trying to identify the nose is which is really distinctive that I just can’t I can’t identify

RB: You’re getting these rancio your notes you can liken it to your malmsey, definitely to your Spanish style sherries but there’s a zingyness a sort of tartness so you get all these notes of apricot’s and hint of tamarind notes. I would say that was probably a semi-secco. These are superb casks for finishing rum, whisky or tequila. It would be nice to put marsala a bit more on the map as it probably being left behind due to its geography out there on the tip of Sicily so you know I definitely recommend a marsala finish and we can help you with that.

CP: Then I think we’ve probably just got a couple more the next one was Muscat if you wouldn’t mind talking us through this one

RB: Muscat is a very interesting family of grapes widely used in France for vin du naturelle. There are two principal varieties you find around the world in quality VDN or fortified wines: muscat vin to petit vin wine (white small berry muscat) producing the finest muscats But there are very few of those muscats aged in oak as they are bottled fresh, zingy, fruity and young. They are still fortified wines but not too relevant to the wood side of what we’re talking about today. So we have to go further afield from France to really look at how Muscat is used in slightly different context so you got here in list actually in front of us we’ve got Moscatel de Setubal from just South of the Lisbon area in Portugal and also Moscatel del Doro which is made in the same area as port wine. So these moscatel (by the way Muscatel Muscat, Moscato is all the same just different languages) when you age oxidatively and in a hot climate in wood for several years the difference between a the muscats are huge. So this is a oxidised oxidative style muscat I haven’t touched the montilla it’s very closely related to sherry as its next door. It’s been oxidative aged so you’ve got these amazing fruity flavours, you’re getting definitely apricot even strange enough of orange which is not always that common. And you’re getting those cooked and rancio flavours as well you know PX territory don’t you think ?

CP: Did you say there’s sugar added?

RB: No it’s can be but then it wouldn’t be a fortified wine, in this case the fermentation is interrupted by the addition of alcohol (grape spirit) which is why it’s so deliciously sweet. It’s really good, so much going on so I always recommend muscat as I finish you know instead of PX there’s more fruitiness than PX. PX has prunes and dried raisins this this is sort of not too old oxidised muscat you getting them but also apricot, melon and mango even.

CP: I agree with that the orange and the apricot… it almost reminds me a little bit of Grand Marnier you know it’s like a liqueur, like an orangey liqueur but not quite the same.

RB: So these are aged in solera-like butts, sometimes in smaller casks all around the Andalucia area.

We have zibibbo which is Alexandrian Muscat which is the second most common Muscat grape very close to marsala in fact those wines are oxidatively aged, sometimes young but it’s a fortified Muscat. We supply a lot of those casks, At the bottom there for our Australian friends we’ve got Rutherglen Muscat which has a longer history than people realise. Rutherglen was actually founded by the guy who started Penfolds Wine and I think for many years they just produced these sweet wines which the Australians call ‘stickies’ so they produced these down in Australia emulating the European way of doing things for you know 150 years or so. Rutherglen Muscat is very expensive very very limited volume wine if you get chance to try it these are amazing wines. Those barrels are very rare but we do get some every year but very, very, very few so we can’t always guarantee supply those but it’s always worth asking g

CP: So moving on to the final chapter quickly before we run out of time…. Grenache Vin du Naturelle is also from the same regions of France as the Muscat Vin du Naturelle. Grenache is a red grape (or garnacha in Spanish) and these wines are very interesting that are fortified to leave residual sweetness and then they are oxidatively aged. A lot are aged in Bayousse down on the Spanish border there. These are really great wines with rancio notes, oxidatively aged so those are interesting they’re not all aged in barrels or barriques but some of them are and we do occasionally get grenache barrels. Commadaria has a fascinating history which some people believe is the oldest wine in the world. It is a sweet wine which goes back something like 3000 years or something insane. It’s a classic wine made from a local grape called, Xynisteri. It is very similar to a fortified muscat. These are are aged in barrels for at least two or three years and a lot more. Vermouth is an aromatized wine so it’s fiddled around with a lot more than a natural fortified wine by the addition of botanicals and maceration techniques, normally there’s some sort of distillation is going on to some degree. Traditionally these come from northern Italy and parts of France. Quinquina is very closely related to vermouth but the principle flavour is quinine or chincona or quinine extract. Those barrels are very hard to come by, but occasionally we do have some. classic brands of quinquina would be something like Lillet, if you know James Bond that’s part of the famous Vespa Martini formula. Those are actually aged in barrels but not all vermouth is.

CP: I think we went into quite a bit of detail so hopefully that was useful for everyone and we gave you some good ideas. It is true I think to say that casks are a little bit of a minefield for purchasing from distilleries and things. One of the things we’ve seen is some slightly unscrupulous sellers of casks. So Rich as specialists in the area could you give us a breakdown on how you source your casks and assure that quality?

RB: That’s actually right Charlie. You know we’re here because we source quality casks. Sourcing is a minefield and even we learnt the hard way in the early days 10 years ago. There’s a lot of unscrupulous brokers. When you visit cooperages and wineries you will see a lot of old cars kicking around, dry, musty so you gotta be careful you’re not dealing with people who will pass those casks off by sticking port in them for a month and passing them off as port barrels as they won’t be as good quality as you’d expect. You’ll end up with problems like Geosmin and sulphur in low quality barrels. One of the other big problems is when left empty the barrel can develop acetic acid on the staves when there’s no protection from the alcohol which can quickly develop into ethyl acetate through oxidation so you can end up with vinegar. This will bring a nail polish remover and solvent smells. We’ve seen this happen to a lot of poor quality oloroso barrels.

We manage these risks through our knowledge and our experience and above all, through our relationships with bodegas. We are kind of lucky and I suppose that’s how we came into existence… because we have great access into many distilleries around the world as both customers and suppliers. For example, we sell high proof grape spirit to wineries for fortification so we have privileged access to casks and barrels which most brokers don’t really have to the extent that we can roll up and select what casks we want.

CP: Thanks Richard, all that remains really is to say thank you to everyone for bearing with us too for joining we hope you have been slightly entertained or at least informed of some options for ageing spirits in some different types of casks which are out there and they are available through Ethimex.

Please do feel free to contact Ethimex to find out more about sourcing fortified wine barrels for your next project.